The Bob Nichols Story

"My dad, Robert W. Nichols Senior, and his parents, moved to San Diego in 1896. He was one of 9 children and they owned 1 section of land, about 640 acres, in downtown San Diego. My mother, Mary May Lund, came from England around 1905. My mother's father was a captain and owner of 4 clipper ships in the San Diego area and operated several restaurants is San Francisco and San Diego. My dad started an electrical repair business after WWI and he became the first radio and electrical wholesaler in Los Angeles and the Southern California area with 4 buildings. He sold the first box car load of radios and the first electric waffle irons," said Nichols.

Robert W. Nichols Junior was born September 14, 1921 in an area that would later become the city of Hollywood. His father paid $3800, in 1922, for a new house in an area next to Los Angeles called Highland Park and Bob would live there until he turned 18. He attended Buchanan Street Grammar School, then moved on to Luther Burbank Junior High School and graduated from Franklin High School, all in Highland Park, California, in the spring of 1940. "I did not take any shop classes, because I started working in several garages and shops at the age of 11. I worked for free at some of the places for the experience and I remember working for California Auto Bed Shop in 1932 and Booth's Garage on Figueroa Street. I would get paid anywhere from 50 cents a week, up to $2 a week.

I bought my first car, an Overland for $5 in 1935, which I promptly overhauled and painted the engine grey. I spent 2 1/2 years in high school building a model "A" Ford 1930 coupe with a Winfield red head, which had a 7 to 1 compression ratio (flathead). It was manufactured by Ed Winfield, whose shop was in Glendale, California. This Model A would do 53 miles per hour (mph) in low, 80+ mph in 2nd and 111 mph in high. The first guy to beat Archie Kamp and me was Rodger Ward with a supercharged model A with a Ford V8 85 engine as we drag raced our cars. He also went to Franklin High and won the Indy 500 twice," Nichols added.

To earn money during the great depression, Bob mowed lawns for ten cents and that was with all manual equipment as there were no power tools in the 1930's. It would take him two to three hours to finish the yard work. He also washed dishes in a restaurant for 12 cents an hour in the late '30's. His hobbies were backpacking in the local mountains and the sleeping bags that he used were made out of woolen blankets and held together by 3 inch horse safety pins.

His father lent him a 12 gauge double barreled shot gun and he went hunting when he was twelve years old. "The first time I fired it I pulled both triggers which put me on the ground and cut my finger to the bone. I still enjoy hunting, and I went elk hunting for 2 weeks in northern Idaho in 2007 at 86 years of age," he continued. "The reason I had the gun problem when I was 12 years old was my dad had a nervous breakdown in 1929, caused by WWI, the 1929 stock market crash, the depression and other things, and so my mother raised us 4 kids with no dad.

My dad left a closet full of guns which my mother sold, except the shotgun, a gift from his brother, which I still own and use.

After high school, I went to work at AERO ITI (still around), a school for men who wanted to work in the aircraft companies. There were 1200 Okies, Hillbillies, Texans and other groups there. We had a hard time with the English language and I wondered if they were real Americans, with those accents, but it sure helped when I got in the Corp of Engineering in WWII.

My next job was with Douglas Aircraft Company on the first day of 1941, in the machine shop at 37 cents an hour. I worked there until 1964, except of course when I went to war for two years from 1943 to 1945. I started motorcycle racing in 1940 at Southern Ascot Speedway TT course with the great ones like Ed Kretz, Floyd Emde, Chuck Basney, etc, and then in 1941, I started Short track, which was also called Speedway Racing with the world champion Jack Milne, Lammy Lamoreaux, and boy were they great. They always beat me, however I did win the National Class B championship on June 2, 1942 and I still have the cup with my name engraved on it," Nichols continued.

“The greatest generation America ever produced needs to be viewed from the 1920-1940 depression years life style. The life style was survival on almost no money. We could not follow fads in clothes, shoes, eye glasses etc; however, we were a very lucky family because we nearly always had enough food and one good set of Clothes for going to church at least two times a week and twice on Sunday. However, there were a few exceptions, because once or twice a year we had real home made root beer and hand cranked ice cream. We bought the Hires root beer extract for 35 cents, which made five gallons and took three weeks to cure. We bottled it in old wine bottles which were hard to find. We also had to borrow a capping device for bottling from someone who had been into bootlegging, this was around 1930.

There were no school buses in Los Angeles 60 and 70 years ago, so we walked and some times ran the 1/2-mile and later the 2 miles to school. Most of us were poor, which included farm kids as well as us city kids. We almost all went barefoot all summer and a month of school, when we could talk our mother into it. If you were a younger son, you wore hand-me-downs clothes.

I sometimes mowed lawns for 10-cents; it took about 2 to 4 hours and was all done by hand there were no edgers. The real problem was to find someone who even had an extra dime. When I got to junior high school I started running every day and later on, in high school. I noticed my legs were better than most of the football players. In high school we had cars, mostly model-T Fords or maybe a Model-A (now worth $10,000 to $20,000). We paid as low as $5 dollars to $35 dollars, but we still walked to school, because gas was 10 to 12 cents a gallon,” Nichols told me.

“The only traveling we did was by street car at 7 cents fare and you could go 30 to 40 miles from home.

Then in the early 1930's, we had a real train trip to San Diego on a coal burner that put cinders in your eyes if you looked out an open door between the cars or slid open a window (this was air-conditioning), which I did and of course it did hurt. The train station in San Diego still had gas lights and I still remember thinking I was back in the 1890's or so. I did a lot of hiking and hunting in those young years.

We also learned to surf in 1932-33 at Long Beach and Huntington Beach. I was 12 years old and not too good at it. At age of 16 my brother John and I started going to the beach, starting early and mostly hitch hiking or by street car to spend the day bodysurfing. We lunched at a cost of 25 cents for both of us. We got a loaf of white bread, half a pound of bologna and a quart of milk, and of course we ate it all. We didn't do board surfing, because you needed a car to carry a 12 or 14 foot long paddle board and the cost was too high. I worked in junior and senior high school, some of the time you did not get paid, because you where expected to learn some skills first. There were plenty of men who would work for 10 to 25 cents an hour in those days.

Of course, we all did lawns at 10 cents and sold newspapers and magazines at 1/2 to 1 cent each, however my first real job was in an upholstery and auto-bed shop. I was about 12 years old, and I would hang out after school and work for free,” Nichols continued.

“The start of World War II for me was September, 1944 at the red street car depot in downtown Los Angeles where we got a physical exam and then quickly boarded a red car to Fort MacArthur in San Pedro, California. This was the beginning of a great adventure and travel for me. I was happy about the future; little did I know what was in store for me.

I did not have to go to war, but I was the only one left without a 4F rating out of 60,000+ at Douglas Aircraft Company in Santa Monica California, so I quit to get into the service. It took two months to finally make it in. I had two good jobs in the two months I had to wait. The first job was for Joel Thorne, a millionaire and Indy racer doing lofting for the Thorne car, which he sold after WWII to Tucker. It was then called the ‘Tucker car.’ I didn't get paid, but I learned what a really good car should be. The next job was a fair sized machine shop in which I became foremen after one week and got big money, but that is another story.

The next move was a big one on a train all the way to Louisiana in the Deep South. This was very slow, about 7 days and the first shock was Texas where we could see the signs from the train window that said, ‘Colored only,’ at the drinking fountains and restrooms. This was new to me and it was wrong. I always had a bad feeling about the South after that and living there 5 months only made it worse. It was a shocker for a So-Cal person. This did not seem like America, neither did Louisiana with its heat and jungle like areas and it turned out to be worse than any of the many Islands in the South Pacific, of which I visited about ten of them,” Nichols went on.

“I had planned on joining the paratroopers as I stood in line at Fort MacArthur, so I talked the doctor into changing my height to six feet, instead of 6'-2 1/2," which was a requirement for the paratroopers. The next day it was all canceled, because they had just released 30,000 air force officers, which were considered excess. So I became part of the Corps of Army Engineers. This was the best for me and the army, now that I think about it 60 years later. I arrived at Camp Clayborne, Louisiana; it was the largest Engineering Camp in the USA, with fifty square miles and I walked a lot of it. Now basic training for the Engineers was rough and tough just like any combat riflemen took. I thought the Corps of Engineers was going to be easier with learning about engineering, and that did come three months later. The one thing we all learned quickly was how different we all were, and especially being from So Cal.

There were the ‘you all’ boys who talked slow and the city slicker types from New York who believed they knew it all, and the really tough guys from Chicago. We all said we would buy a surplus tank to visit them after the war was over. The basic training was very tough on most because they had not done hard work or been in sports to toughen up. So for most it was to bed after an exhausting day of training. For me it was the heat with the high humidly from 80% and 90% most of the time. I had lived at the beach, and I worked the 2nd shift, and I went body surfing, swimming and running every day until 3 PM and then to work at 4 PM till 12:30 AM, 7 days a week during the war time period from 1941 to 1944,” he said.

“We had several highlights in basic training. The Red River rose over the dikes to the 2nd story of buildings in the town of Alexandria, and as engineers it was our job to stop the flooding. We worked 24 hours a day for three days with bulldozers, drag lines, dump trucks, pick and shovels and a lot of sand bags. We used the main highway for fill on top of the dikes. I remember the concrete was about 2 to 3 foot thick. After basic training we were each assigned to one of many different engineering functions such as; pipe lines, bridges, road building, etc. For me it was ‘water purification and supply.’ We spent the next three months learning to make water from rivers, lakes and also to run the city water supply system. We would take our 2 and a 1/2 ton water truck and jeep and pump water into 500 gallon canvas water tanks from a bayou. These usually were about 30 to 100 miles from camp on one-way dirt and mud roads. It was always quiet and there were no farms or houses, just heavy pine forests with deep creeks about 8 to 12 feet deep and about 6 to 14 feet wide. You had to jump across because it was to steep to climb them. These channels were spaced 100 yards to 1/2 mile or more apart. After we set up the canvas water tank (500 gallons) and started the portable water pump we would start hiking to look for wild pigs and old houses. Often when the water was being pumped, several G.I.s would take a nap, and this was the time for a real hot foot. It was a real eye-opener due to the heavy boots and many laces made them slow to take off, which was necessary due to the extreme heat. No one ever knew who did the evil deed because of the many pine trees we would hide behind. It was a great pastime for a lot of G.I.s in WWII. I was on both ends of the match and had a few laughs,” Nichols continued.

“When in the process of getting out of the Corp of Army Engineers, I had a shocker. I was called into the Colonel's Office. What had I done! Everyone else was checking out by the thousands each day. I knew I was in trouble, because of a few items taken at midnight from the Air Force motor pool. My past was catching up with me. So down I went to see the Colonel. My heart was sinking and I thought ‘what could it be,’ as I could land in jail or worse. The office was small; the Colonel had in his hand my MOS (military operational skills) card. He asked me what I did during the war and I answered that I was trained to be a water purification and supply technician. However, I had been trouble-shooting on gas and diesel engines on the island of Tinian. The island was 4 miles wide by 11 miles long, with over 100,000 people and 500 B-29 Aircraft on it. I had been fixing engines for 32 water wells and 1000+ generators. The Colonel then asked how it was possible that I have been a machinist, tool maker, small gas engines mechanic, heavy duty engines mechanic and Army riflemen. It was not possible to have five MOS in the Army he said. At this point I was feeling a lot better and I explained how I started at eleven years old in garages, then later was a machinist, then building Ford model A hot rods, racing Indian and J.A.P. Speedway bikes, plus being a wind tunnel model builder at Douglas Aircraft Company and finally a machine shop foreman at age 23. The next day the Colonel discharged me from the service,” Nichols said.

"I remember building an oval race track and a 45” Harley for racing on the island of Tinian, where the atom bomb was transferred to the Enola Gay, a B29 Bomber on the island. I was not drafted. I quit Douglas aircraft Company in 1943 to join the service, and I wanted out of the great banana factory. I started in the paratroopers and ended up in the Corp of Engineering and spent almost two years in the service in the Pacific. My job overseas was chief trouble-shooter on the island of Tinian. The engines were small, 1 cylinder in size up to huge diesels with 3-1/2 foot diameter pistons and it was hard work and very hot weather. Tinian had 500 B-29 bombers and 100,000+ men, all on a 4 mile wide by 11 mile long island. But I enjoyed diving and swimming every day, and most of all racing my Harley against a few bikes and a lot of cars, especially Jeeps on my track every day till dark,” Nichols went on.

“I got married in 1943 using my brother's Model-A Ford to drive to Las Vegas. Her name was Stacia and she was the most beautiful woman in the world. The whole trip cost about $15 or less. Then in 1944 my first daughter, Marna Jean Nichols was born in Glendale, California, while I was still in the Army. My next daughter, Belinda Annette Nichols, was born in 1947, in San Bernardino, California. Then in 1951, I bought a home for $13,000 in Culver City, California, which I sold in 2003. Stacia passed away and in 1964 I married my second wife, June and we’ve been married every since. I married two beautiful women. During this time I worked for Douglas Aircraft Company in Santa Monica, California, for 24 years. I have one grandson, Ryan Nichols, born in 1985. I am proud of how well he is doing.

In 1964, I designed and machined the first titanium connecting rods for George Bignoti, the mechanic for A.J. Foyt’s Offenhauser. Foyt won the Indy 500 in 1964. Then in 1965, I designed and machined the first cam followers (buckets) for the S & W Triple wrap Valve springs for Dickie Jones at Champion Sparkplugs in Long Beach, California. These Offenhauser buckets were heavy with .125 walls, so I used maraging 350 steel which allowed .028 walls to reduce the weight. The dyno tests added 50 HP. The year 1966 was big for Mickey Thompson, because I detailed the blue prints and machined the heads and cam towers for the double over cam Chevrolet Aluminum block engines for Indy. At 86, I am still racing my two Indian Sport Scouts in the AHMRA tracks around the USA and at the Dry lakes at the SCTA time trials at El Mirage Dry Lakes, near Phelan, California. My current efforts are designing and using CADD software systems for race parts and cams, however I do designing and machining for race parts and cams on my two Indians racers," Nichols concluded.

Richard Parks, Gone Racin' is at RNPARKS1@JUNO.COM

This story has been republished by permission of Richard Parks of HotRodHotline.com, the world's largest online rodding magazine. Visit: www.HotRodHotline.com

Richard Parks

Roger Rohrdanz

Bob Nichols (2008) showing off his machining handy work.

At home in his shop. (2008)

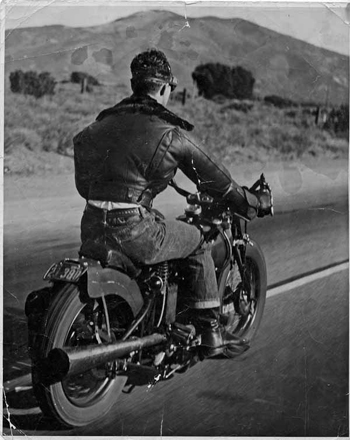

Bob Nichols on a Sunday ride in Soledad Canyon, CA with Kenny Schofield and Lammy Lamoreax. Circa Oct. 1942

(R. Nichols collection)

Robert Nichols, 1939.

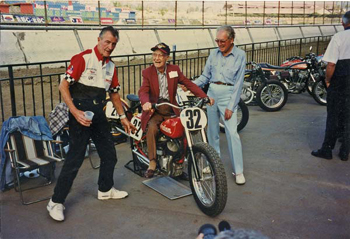

Bob Nichols (l) Jim Davis on bike is 101 years old, former "Big Bike" Champ. Circa 1996 Del Mar Nostalgia race.

(R. Nichols collection)

Bob bike testing at El Mirage. (2004)

(R. Nichols collection)

Ernie Bose (l) and Jim Robinson

hang out in Bob Nichols shop. (2005)

Circa 1941, J.A.P. bike (James Arthur Preswick)

(R. Nichols collection)

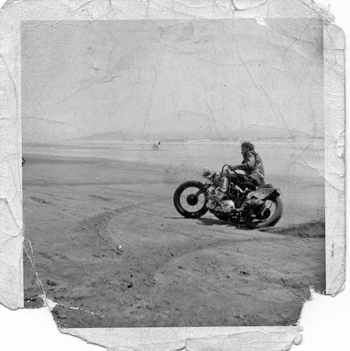

Bob doing figure 8’s at Pismo Beach, CA circa 1942.

(R. Nichols collection )

Getting ready to race his 45 cu in Harley, a daily affair for cars and bikes, and on the island of Tinian, where the atom bomb was transferred to the Enola Gay, a B29 Bomber on the island. (R. Nichols collection)